Study Areas

David and Elizabeth Harris, Underground Railroad Stationmasters

David and Elizabeth Harris headed one of Harrisburg's most prominent families in the decades prior to the Civil War. David, a grandson of borough founder John Harris, was a businessman who also held various positions of importance within the borough administration, including that of burgess. He married Elizabeth Latimer, of York and they raised five children in a circa 1802 log weatherboarded house at 117 South Front Street in Harrisburg. The property then included outbuildings, including a barn. It was here, in the barn, that they provided a stopping point for fugitive slaves moving through Harrisburg.

Sallie Harris, daughter of David and Elizabeth and the last of the family living in the house by the time of her death in 1928, gave the only known information about this little-known Underground Railroad station. In interviews conducted just prior to her death, she told of how her mother, Elizabeth Harris, would provide food and clothing to the freedom seekers, then arrange for their safe passage to another station along the route north. Sallie noted that "scores" of fugitive slaves were sheltered "at various times."

David Harris is identified in her reminiscences as a "burgess," at the time, who turned a blind eye toward the activity. More research is needed to identify the years and actual positions he held. Historian Henry Egle identifies him as a burgess in 1847, and other biographical sketches note he was a justice of the peace. It is also not clear if Sallie Harris, who was born in 1846, witnessed any of these Underground Railroad activities or learned of them later. She would have been four years old at the time of passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, and certainly old enough to witness and recall the details of any activity in their household during the mid and late 1850s, a time when many fugitive slaves were moving through Harrisburg.

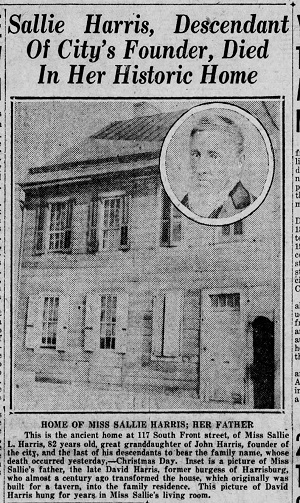

At right is the 1928 news article that identifies the David Harris family as Underground Railroad stationmasters. A photo of the home at 117 South Front Street, along with a photo of David Harris, heads the article.

Full text of the news article:

Sallie Harris, Descendant of City's Founder, Died in Her Historic Home

(Photo of Front Street home, with an inset portrait of David Harris)

Photo caption: HOME OF MISS SALLIE HARRIS; HER FATHER

This is the ancient home at 117 South Front street, of Miss Sallie L. Harris, 82 years old, great granddaughter of John Harris, founder of the city, and the last of his descendants to bear the family name, whose death occurred yesterday, -- Christmas Day. Inset is a picture of Miss Sallie's father, the late David Harris, former burgess of Harrisburg, who almost a century ago transformed the house, which originally was built for a tavern, into the family residence. This picture of David Harris hung for years in Miss Sallie's living room.

Miss Sallie L. Harris, 82, great granddaughter of John Harris, founder of Harrisburg, and the last direct descendant bearing the Harris name, died yesterday afternoon at the old family homestead, 117 South Front street, after being ill with pneumonia for four days.

Miss Sallie suffered a severe shock early last week when Catherine Davis, a colored maid, who had long served in her household, died at a Harrisburg hospital. It is believed that the shock caused by the maid's death, which followed a brief illness, hastened Miss Harris' death.

Private funeral services will be held on Friday afternoon at 4 o'clock at the Spicer funeral parlors, 511 North Second street. The Rev. Dr. Henry Little, acting pastor of the Market Square Presbyterian Church, of which Miss Harris was for many years a member, and Miss Sallie's nephew, the Rev. Hugh Latimer Willson, of the Philadelphia Divinity School, will officiate. Burial will be in the Harrisburg Cemetery.

Born in 1846

Miss Harris is survived by a nephew, Thomas H. Willson, of Haddonfield, N.J., assistant treasurer and registrar of the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, Philadelphia, and the latter's sons, David Harris Willson, of the faculty of the University of Minnesota, and the Rev. Hugh Latimer Willson.

Among the more distant relatives are Miss Mary Harris Pearson and William Pearson, whose mother was a third cousin to Miss Sallie. They are direct descendants of the founder. Mrs. Robert G. Goldsborough is a third cousin of Miss Harris.

Miss Sallie, as she was better known to her relatives and friends, was born on October 5, 1846, in the old house where she passed away.

Turn to Page Fifteen

Continuance of article on page 15:

SALLIE HARRIS DIES; 82 YEARS

From Page One

Miss Sallie and her sister, the late Mrs. Louisa Harris Willson, of Haddonfield, N.J., received their education in the school conducted by Miss English, in the building in South Front street, where Mrs. Gifford Pinchot, while her husband was Governor of Pennsylvania, recently conducted a special school.

The old homestead, which was built in 1802, was first conducted as an inn. When Miss Sallie's father, David Harris, married, he purchased the tavern and converted it into a home.

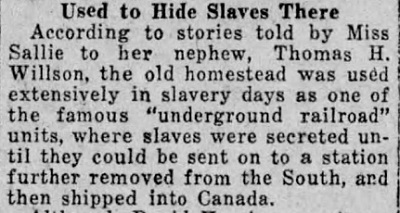

Used to Hide Slaves There

According to stories told by Miss Sallie to her nephew, Thomas H. Willson, the old homestead was used extensively in slavery days as one of the famous "underground railroad" units, where slaves were secreted until they could be sent on to a station further removed from the South, and then shipped into Canada.

Although David Harris was at one time burgess of Harrisburg, and supposed to use his authority in catching runaway slaves, scores of slaves were hidden at various times in the barn of the old homestead where Mrs. Harris supplied them with food and clothing and later had them sent further North. Miss Sallie inferred that her father, Burgess Harris, unofficially was cognizant of what was going on, but so long as it was not officially brought to his attention, he just winked at the comings and goings of the runaway slaves.

The Harris homestead was purchased several years ago by the Harrisburg Hospital, when Miss Sallie became a life tenant, paying a yearly rental of $1. It was stated that Miss Sallie made quite a ceremony of the payment of th rental, for which she always received the regulation receipt. On one occasion the life tenant became considerably worried when she failed to receive the receipt, whereupon she notified her relatives of its non-arrival.

With her death the property reverts to the Harrisburg Hospital. The furniture will be taken over by Thomas H. Willson, her nephew. The latter today said he was unable to place any value on the contents of the house, which includes many rare pieces pf furniture and other antiques.

The value of the furniture will probably never be known inasmuch as none of it will be placed on sale. The nephew said that a portion of the furniture will be given to those friends who may appreciate it more from its sentimental value than its value in dollars and cents. Among the furniture is a walnut table, made by John Harris, the founder, in 1760. The table is equipped with wooden hinges and shows the qualities of a master workman.

Willson has in his possession a lead inkstand, also made by the founder. The led pot was carved out by means of a penknife, according to the owner. Another rare piece is a parlor lamp made of anthracite coal and once, used for burning whale oil.

On the mantel of the sitting room were several pieces of steel scroll work which were obtained when the Market Square Presbyterian Church was destroyed by fire many years ago.

Miss Sallie's nephew was unable to give the date when the church was burned, nor what part the ornaments played in the church building.

Gracious In Recent Interview

Although Miss Sallie was reputed to be very distant and aloof and very reticent in discussing her own affairs, such was not the case several weeks ago when a reporter of THE EVENING NEWS gained an interview with her. She was most gracious in her attitude toward the news gatherer and freely volunteered much information about herself and her historic forebears. She fairly sparkled with wit and merrily laughed as she told of episodes in the lives of the Harris family.

Members of the family today said that Miss Sallie had thoroughly enjoyed the interview. She mailed clippings from THE EVENING NEWS to her relatives.

(The Evening News, Harrisburg, PA, 26 December 1928, pages 1 and 15)

Notes

The home featured in the article sat at the southeast corner of Cherry and Front Streets in Harrisburg. The lot was originally property of Robert Harris, father of David Harris, and was sold circa 1791 to a Mrs. Stehley, a widow, who built a two-story weatherboarded log inn, which she managed for several years. The building passed through several owners and was used as a store until it was purchased by David Harris and renovated for use as a family home. It remained in possession of his family until purchased by Harrisburg Hospital as noted in the article above. The present site is occupied by Harrisburg Hospital.

Although at this time we have no corroborating sources, Sallie Harris' story contains details that lend veracity. She says fugitive slaves were hidden in a barn on the property, and not in the house. This is consistent with typical practice of the time. Her mother supplied food and clothing to the freedom seekers. Ads for escaped slaves nearly always described in great detail the clothing they wore, since it was a quick way to identify them. Enslaved persons from Virginia and further south often wore only "negro clothes," clothing made of cheap undyed material and lacking any ornamentation, tailoring or fashion. A change of clothing, then, could be as important as a meal to those pursuing thier freedom. It also deos not suggest that the Harris' took the fugive slaves to the next station, but that they were "sent." This may have been as simple as instructing them on how to find the next station, or more probably it involved arranging for local African American conductors to take charge of them.

Sources

- "Sallie Harris, Descendant of City's Founder, Died in Her Historic Home," Evening News, Harrisburg, PA, 26 December 1928, pages 1, 15.

- Egle, Henry, "Notes and Queries," The Telegraph, Harrisburg, PA, 03 December 1887, page 5.

- "Sally Harris Letter," The Telegraph, Harrisburg, PA, 26 August 1927, page 4.

- "Death of Mrs. David Harris," The Telegraph, Harrisburg, PA, 19 January 1894, page 1.

- "David Harris," The Telegraph, Harrisburg, PA, 15 March 1880, page 4.

- 1850 Census of the United States, South Ward, Harrisburg Borough, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, page 10, 16 August 1850.

Now Available on this site

The Year of Jubilee

Vol. 1: Men of God and Vol. 2: Men of Muscle

by George F. Nagle

Both volumes of the Afrolumens book are now available on this website. Click the link to read.

The Year of Jubilee is the story of Harrisburg'g free African American community, from the era of colonialism and slavery to hard-won freedom.

Volume

One, Men of God, covers the turbulent beginnings of this community,

from Hercules and the first slaves, the growth of slavery in central

Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg area slave plantations, early runaway

slaves, to the birth of a free black community. Men of God is a detailed

history of Harrisburg's first black entrepreneurs, the early black

churches, the first black neighborhoods, and the maturing of the social

institutions that supported this vibrant community.

Volume

One, Men of God, covers the turbulent beginnings of this community,

from Hercules and the first slaves, the growth of slavery in central

Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg area slave plantations, early runaway

slaves, to the birth of a free black community. Men of God is a detailed

history of Harrisburg's first black entrepreneurs, the early black

churches, the first black neighborhoods, and the maturing of the social

institutions that supported this vibrant community.

It includes an extensive examination of state and federal laws governing slave ownership and the recovery of runaway slaves, the growth of the colonization movement, anti-colonization efforts, anti-slavery, abolitionism and radical abolitionism. It concludes with the complex relationship between Harrisburg's black and white abolitionists, and details the efforts and activities of each group as they worked separately at first, then learned to cooperate in fighting against slavery. Read it here.

Non-fiction, history. 607 pages, softcover.

Volume

Two, Men of Muscle takes the story from 1850 and the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850, through the explosive 1850s to the coming of Civil War

to central Pennsylvania. In this volume, Harrisburg's African American

community weathers kidnappings, raids, riots, plots, murders, intimidation,

and the coming of war. Caught between hostile Union soldiers and deadly

Confederate soldiers, they ultimately had to choose between fleeing

or fighting. This is the story of that choice.

Volume

Two, Men of Muscle takes the story from 1850 and the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850, through the explosive 1850s to the coming of Civil War

to central Pennsylvania. In this volume, Harrisburg's African American

community weathers kidnappings, raids, riots, plots, murders, intimidation,

and the coming of war. Caught between hostile Union soldiers and deadly

Confederate soldiers, they ultimately had to choose between fleeing

or fighting. This is the story of that choice.

Non-fiction, history. 630 pages, softcover.